|

FANSHIP DESIGN & STATS: Brad R. Torgersen,

2006

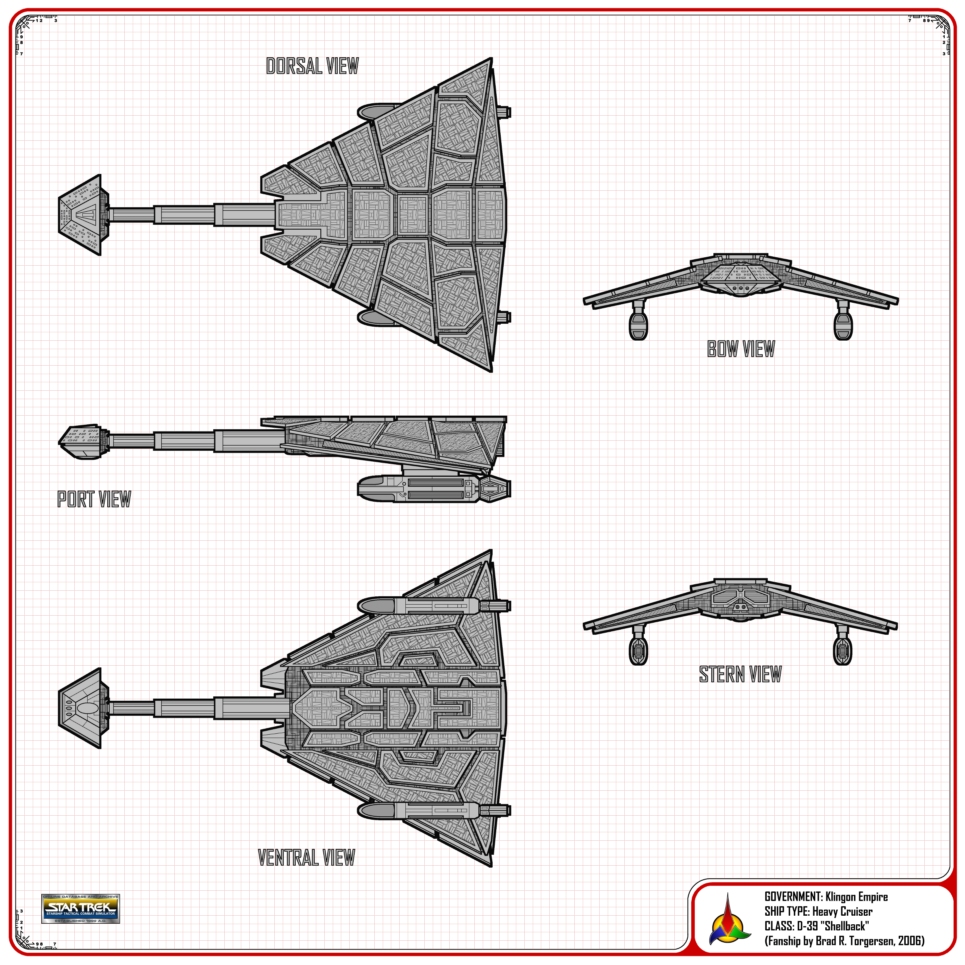

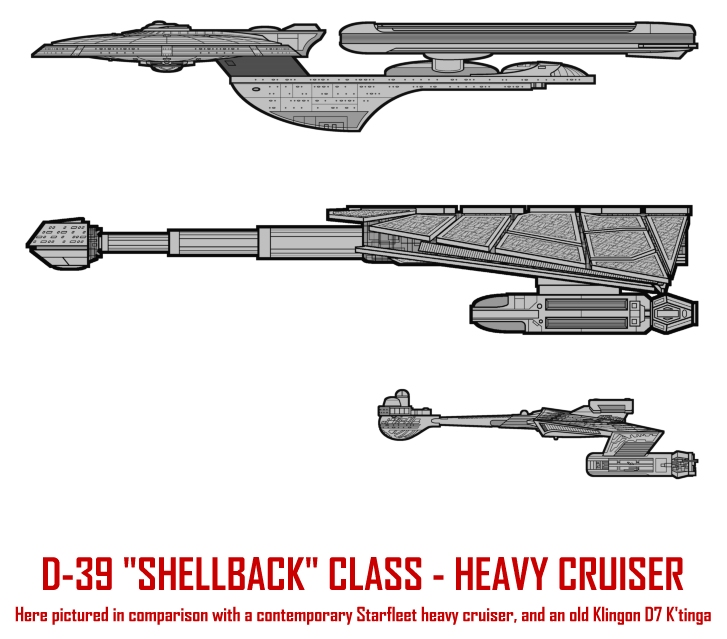

"Shellback" class XIV-XV Heavy Cruiser

NOTES: At the time of its conception in 2287 A.D., the D-39 was to have been

among the

largest operational warships in the Klingon Imperial fleet; larger even than the

sizeable L-24 design, and

envisioned as a direct response to the Federation's prototype

Excelsior class.

Known commonly to Starfleet personnel as "The Wedge" or

"Shellback", much of the D-39's early history is bound up in the

interstellar tumult of that period.

Having engaged in a decades-long,

undeclared, hot-cold conflict with the United Federation of Planets, the Klingon

Empire at the end of Earth's 23rd century, was a nation in deep crisis. Infrastructurally exhausted, and blocked in on two lengthy borders by both the

vexing UFP and a former ally—the mercurial Romulan Empire—many Klingons were

deeply afraid that their government and their way of life were both about to

crumble. Attempts to overmatch the Federation—technologically,

logistically, militarily—had met with either stalemate or failure.

Science and engineering exchanges with the Romulans, which might have offset

lagging Klingon advancements, had largely ceased. For many officers in the

Klingon military, as well as rulers of the powerful Houses, and officials on the High

Council, there seemed but two choices left: open war with the Federation and/or Romulans, or allow the other

great Alpha Quadrant powers to slowly suffocate the Empire under a blanket of

placations, treaties, and the gradual erosion of Klingon Imperial sovereignty

before a hostile interstellar consensus.

Those proposing open war gained significant traction in the Empire when it was

revealed in 2285 A.D. that Starfleet had test-detonated a new super-weapon in the Mutara Sector of Federation space. The Empire quickly poured

resources into its intelligence network inside the UFP, eventually identifying

the super-weapon as a high-level civilian research project dubbed Project

Genesis. Not much was known about Project Genesis, save for the fact

that the detonation in Mutara was draped in a veil of Starfleet secrecy—a veil so thick

not even the stealthy Orion information traders could penetrate it.

Multiple close-border recon patrols were launched, using deep-field subspace

collectors to sieve Federation comm traffic for more clues as to the design and

potency of Genesis. And a handful of incursion sorties were made using advanced Klingon scout vessels under operational cloak. One such mission managed to

penetrate all the way to Mutara and see the results of the Genesis test

first-hand, before its crew and commander were dispatched by the infamous

human Starfleet Admiral, James Tiberius. Kirk.

The mission was not a total failure, however, as both

Kirk and the Federation Council were forced to divulge the details of Project

Genesis before an open interstellar inquiry. Thus the UFP was politically

weakened when the Klingon High Council, through its ambassador corps on Earth,

charged Starfleet with warmongering and violation of interstellar law through

the development of the Genesis Torpedo. Caught off balance, the

Federation President and his Council were forced into a series of hedge

maneuvers against outcries from governments both outside and inside the UFP,

while the Klingons played the victim card, and readied their fleets for war.

Thus the call went out to every great Klingon design

consortium: find an answer to the Excelsior!

Specifications on the Excelsior class, and what

little was known about Transwarp theory, were widely distributed to all

interested parties, along with the promise of significant Imperial tax credits

and guaranteed military purchase orders for those designer(s) and engineers able

to come up with ships and/or engine technology which would match, or even best,

the impressive Excelsior. Tens of different designs for advanced

hulls were turned in before the end of the Imperial year, and several warp field

innovators made claims that they had, through decryption of Starfleet

documentation still being collected, cracked the secret of Transwarp.

There was one eccentric scientist who even claimed to have cracked Genesis

itself, but by mid 2286 A.D. it became apparent that not even the Federation

had mastered Transwarp, to say nothing of Genesis; both projects having been

dubbed "failures" in advanced UFP research circles.

Still, mounted with conventional warp,

torpedo, and phaser technology, the Excelsior was a formidable foe,

outclassing Starfleet's existing battle-cruiser benchmark, the

Constitution

refit hull, by

several orders of magnitude. At that time there was nothing else in the

Klingon inventory to match the Excelsior class, so the call remained for an

entirely new, hopefully revolutionary hull design which could incorporate the

latest Imperial technology and weapons, and give the Empire a fighting chance

against its largest political adversary.

By the end of 2287 A.D. the Klingon High Command had

culled its choices down to a half-dozen different battle-cruiser and full

battleship designs, at which point the traditionally politicized and

intrigue-laden selection process began to turn decidedly cut-throat.

Recognizing that the consortium chosen to build the new battleship would likely become

the premier Imperial hull supplier for many years to come, each of the consortiums

with hull designs still on the table—and each of the Houses within those great

consortiums—quietly went to battle with one another. Bribes turned into

threats, and threats turned into assassination attempts, both successful and

unsuccessful. Factions began to form on the High Council, and the alliance

against the Federation threatened to fracture before even a single shot had been

fired. Had it not been for the ascension of the wise and politically adept

Chancellor Gorkon—following a combined bribe/assassination scandal which

dishonored the previous Chancellor—it is probable that the Klingons might have

faced a small-scale civil war.

But the rise of Gorkon was timely, for he not only

massaged the variously heated and competing egos involved in the design

process, but reined in corruption on the High Command and the High Council as

well. So that he could turn his attention fully

to the matter of dealing with the UFP, whom it was assumed was months or even

weeks away from launching major military operations across the Klingon/Federation

Neutral Zone.

Gorkon was a visionary, patient man. A pacifist—almost universally alone on the Council—he knew it would take years to slowly,

imperceptibly bring his Empire back from the brink of a war which he believed his people could not win. Intelligence gained in 2288

and 2289 A.D. aided Gorkon's efforts, when it was shown that, contrary to

aggressive speculation, the Excelsior class was in fact not being

mass-produced as part of a war buildup. Only a handful of the advanced

Starfleet ships had been produced to that point, each being dispatched on a

variety of relatively benign science missions, most of them far from the Klingon

territories. So, much to the chagrin of the competing consortiums, Gorkon used

this evidence to put the Klingon-Excelsior contract on hold, and then, slowly,

he buried it in a shallow grave of bureaucratic entanglements. Only the

existing L-24 battleship design was to continue production, and then, in fewer

numbers than had been dictated by the previous administration. By the time

the Klingon moon Praxis exploded, Gorkon's plans for détente with the UFP were well

advanced, and Praxis, like all crises, formed the basis of opportunity for Gorkon's diplomatic masterstroke: an official coming-to-terms with the UFP, so

that as partners, not opponents, they could meet the crisis, and overcome it.

The Gorkon period nearly ended in disaster, however, as

warmongering parties within his own High Command successfully staged Gorkon's

assassination, pinning the blame on the hated James Kirk and lurching the Empire

back towards war. It was only Kirk's rapid action—and that of his fellow

officers and comrades, combining with the foresight of Chancellor-inheritor Azetbur—which averted an all-out clash between Starfleet and the Klingons.

In the process, most of the conspirators in the High Command who had had Gorkon

killed, were either themselves killed, or captured and later sentenced to

dishonorable deaths. The Camp Khitomer summit was thus saved, and the

eventual signing of the Khitomer Accords was to prove a watershed moment in

Alpha-Beta Quadrant political history.

Ironically, it was the aftermath of Khitomer which was

to revive the Klingon-Excelsior design contest, and bring the shelved D-39 back

to the front burner of Klingon Imperial design plans.

The signing of the Khitomer Accords was to have two

direct consequences for the Empire. First, a good many Klingon officers

and crews were none too keen to join hands with their hated adversaries:

Starfleet and the UFP. Second, the quasi-neutral Romulans cut nearly all

official contact with the Klingons, and assumed a state of undeclared hostility towards the new

Federation-Klingon alliance. This meant that the Empire had to quickly

redirect military strength towards its border regions with a former ally, while

at the same time stepping up internal police efforts to quell rebellion among

the ranks. All of which had to happen while the homeworld, Quo'nos,

underwent evacuation and reconstruction on account of the Praxis disaster.

It was a time of tremendous peril for Azetbur and her Council, along with the

newly reformed High Command, and Azetbur directed the resurrection of several

military starship projects in the hope that the latest Klingon war

technology could be marshaled to the Romulan border, and also be employed in striking

down the many traitorous officers and ships which had begun to flee the

Imperial fleet and prey on not only allied UFP targets, but Imperial

targets as well.

From the original half-dozen hull designs left in the

stalled Klingon-Excelsior contest, the High Command—in agreement

with the High Council—selected the D-39 for a variety of reasons. Not the least

of which was the fact that the original consortium responsible for the design

had agreed, under pressure from Azetbur, to subcontract construction to several

of the other major shipbuilding Houses in the Empire. Something none of the

other consortiums had been willing to do.

The D-39 also had the influential input of a man once

banished from the halls of power, but newly recovered in his capacities following

the death of Gorkon, and the events leading up to the signing of the Khitomer

Accords.

By the time of the Praxis explosion, disgraced Klingon

General Korrd was still on assignment as Imperial Ambassador to the wastes of

Nimbus III. Continuing in his role as Paradise City's resident fat drunk, Korrd

might have decayed there for the rest of his life, had Chang and his

conspirators on the High Command not summoned Korrd following the assassination of Gorkon. Chang determined that, in the coming war which he was attempting

to engineer, the Empire was liable to need every talented flag officer it could

get. And even though Korrd was greatly diminished in faculty, with some sobering

up his strategic skills could be of great value.

Korrd arrived too late to be incorporated into Chang's

plans, however. When Korrd's courier from Nimbus III reached Quo'nos, Chang's plot had already

been foiled, and many on the High Command were either dead or imprisoned.

This was to prove fortuitous for the old General, as the power vacuum

created by the purging of the High Command forced Azetbur to integrate Korrd

during the rebuild. Realizing the opportunity before him, Korrd entered

into a forced dry spell

and dedicated himself to assisting Azetbur in recruiting flag officers who would

be loyal to the young Chancellor. Korrd was also on good terms with

Captain Kirk, dating to Kirk's involvement in the Nimbus III rebellion of 2287

A.D., and was seen by both the Klingon High Council and Starfleet as a man who

could work across political lines, strengthening the UFP-Klingon alliance and

assisting Azetbur as she moved to recover the strength and prowess of her

Empire.

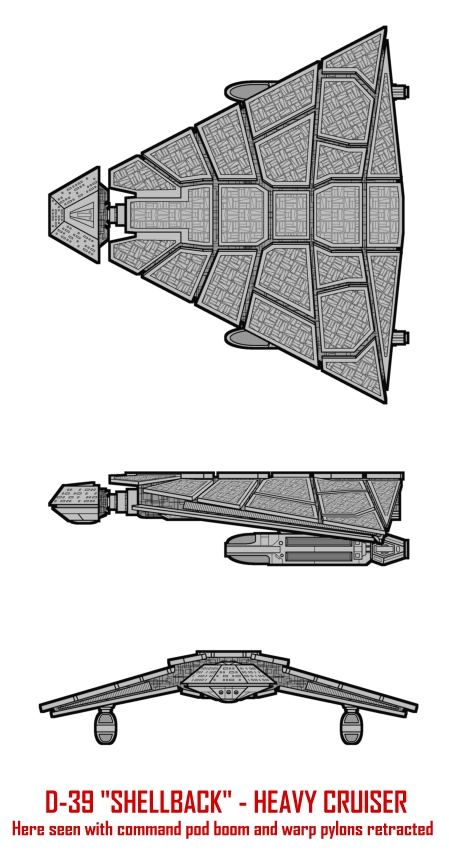

It was in his role as advisor to the Chancellor that

General Kordd made two key suggestions to the D-39 group: the

application of ablative armor plate across the dorsal and ventral surfaces of

the secondary hull, and the employment of a retractable command pod boom, where

all previous Klingon capital ships—including the famed

D-7 K'tinga classes—had used fixed booms.

Korrd's contention, based on

many decades of battle theory and real-world combat experience, was that the

traditional command pod boom, while elegant and flattering to the eye, posed a

risk. Well-placed beam and torpedo strikes could quickly cripple an otherwise able Klingon vessel,

should they damage or destroy the boom on which the command pod traditionally

rested. Korrd spoke from experience, having lost two commands in such a

fashion; each time being forced to limp back towards friendly space on the

strength of his command pod's emergency impulse engines. If the new D-39 could

collapse the boom during battlestations—essentially mating the command pod

directly to the secondary hull—its effectiveness and survivability in a

firefight would be dramatically improved. Both because of the removal of a

potential Achilles Heel, and because a more compact fighting ship would have

greater maneuverability.

The D-39's engineers were highly skeptical of Korrd's

retractable boom concept, as previous designers who had approached such an

innovation had concluded that the retractable boom sacrificed too much internal volume within the secondary hull. To

that point, the centerline bowels of most Klingon ships typically held the primary warp core and/or

adjacent impulse reactors. With life support and other functions being displaced

into the "wings" of the ship, leaving almost no room for superfluous or

gratuitous components like science bays, or the suggested retracting boom. The D-39's engineers were highly skeptical of Korrd's

retractable boom concept, as previous designers who had approached such an

innovation had concluded that the retractable boom sacrificed too much internal volume within the secondary hull. To

that point, the centerline bowels of most Klingon ships typically held the primary warp core and/or

adjacent impulse reactors. With life support and other functions being displaced

into the "wings" of the ship, leaving almost no room for superfluous or

gratuitous components like science bays, or the suggested retracting boom.

But Korrd correctly noted that the entire length of the boom need not be drawn

into the ship. If segmented, the boom could operate much like a

hydraulic jack, collapsing in concentric pieces until the command pod was adjacent in its

entirety to the secondary hull. Korrd also pointed out that the D-39's

secondary hull was large enough,

overall, to house the collapsing boom without significantly

impinging on warp core or impulse engineering. Each of which, while improved in

sophistication over older designs, had not grown that much in total size

compared to older equipment.

And so the consortium

set about drawing up the mechanisms and complicated internal configuration which

would accommodate Korrd's collapsing boom.

Meanwhile, ablative armor, while not new to the Klingon inventory,

had seldom been employed on such a huge scale.

Again falling back on his experience, Korrd pointed out that such "flake-away"

damage-absorbing armor need not be integrated directly into the space hull proper, but could instead be

set apart from the ship's skin on stanchions or spacers, thus creating a vacuum barrier between

the air-tight hull and the armor itself, so that strikes on the armor

would not, in theory, significantly impact the airtight hull at all. Not

only would this greatly improve the combat endurance and survivability of the

ship, but it would also allow much greater turnaround time in drydock, as damaged armor

plates on stanchions could be easily mass-produced, stocked, and

mounted with minimal effort.

Thus, with these two unorthodox design features

incorporated, the D-39 went to prototype.

By the time the

Excelsior Refit class began trials, the

Empire's latest, greatest vessel also made its debut. Sporting a

delta-winged, thick-bodied secondary hull, the D-39 presented a 'scaled' or

'plated' exterior unlike anything that had been seen before. Beyond the

decorative etchings that were so popular on other capital ships, the D-39's

exterior was eminently practical, in that each of the huge exterior plates was

itself composed of myriad, smaller, interlocking ablative tiles, and the

entire surface was set apart from the air-tight hull by a series of uniform

stanchions which allowed the plates to be 'snapped' on or off during drydock

procedures, for quick battle time repair and replacement.

Per Korrd's logic, impact and weapons testing on the plates had shown that even

simultaneous, direct torpedo hits at the same point might obliterate a section

of armor entirely; but the underlying air-tight hull would remain intact, with

only minimal scorching.

The one drawback to using so much armor over such a

great extent of the secondary hull's surface, was the mass such armor added to

the ship's total tonnage. The initial mounting of impulse engines and

reaction thrusters proved inadequate to handle such a heavy craft, and the D-39

"Shelled Predator" (as it had come to be known in Klingonese) had to be taken

back into drydock for several weeks of retooling before it could be sent back

out for maneuvering tests and, hopefully, a first run on the warp drive.

It was during the second set of trials that problems

with the retracting boom began to appear—problems which would persist

throughout the D-39's service life, in spite of numerous attempts to address

them via refitting.

As the D-39's development team discovered, the biggest difficulty with such a

boom, other than

the space consumption within the secondary hull, was that not only did the

superstructure itself have to be concentrically segmented, but all the internal

components, including walkways, turbolift tubes, power conduits, life support

ducts, and other equipment had to be able to extend/collapse as well. This

proved nightmarish for the engineers, who had to force thousands of meters of

conduit, cabling, and ductwork to mate successfully over the boom's three main

pieces. Not to mention enabling the centerline corridor down the length of

the boom shaft, which ran parallel to the turbolift tubes, to remain air-tight and

safe, even during the extension/retraction process.

Time and again, during trials, the inner spaces of the

boom lost air-tight integrity, along with suffering a frustrating host of servo

and motor failures, shorted and severed power leads, and, on three

separate occasions, sizeable fires—the last of which had to be put out by

venting the entire internal volume of the boom to space.

Again the D-39 was taken back into dock, not only for

repair, but for an honest reckoning over the problems the boom was causing.

With General Korrd in attendance, the roundtable of engineers politely suggested

that the retractable neck was simply too complex and finicky a mechanism for

successful deployment on a major Imperial warship. Unless some way were

found to make the retraction process less problematic, the D-39 lay on the verge

of failure.

And so, grudgingly, Korrd suggested that the confines

of the boom be cordoned off during extension and retraction, so that keeping

atmospheric pressure need not be a problem, nor would there have to be any worry

about keeping the turbolifts working. Safeties would be built into the

computer software controlling boom extension/collapse so that turbolifts and

personnel could be evacuated from the boom prior to its activation.

These changes were effected, and the next set of trials

carried out multiple successful retractions and extensions, with all foot and

turbolift traffic down the length of the boom being suspended for the ninety

seconds or so it took the boom's servo system to withdraw or extend its

considerable length into or out of the secondary hull. The process and the

software were refined over a series of weeks until the engineers, and Korrd,

were satisfied that the mechanism was safe for operational use. Though, as

mentioned before, the boom would continue to prove temperamental over the

service life of the spaceframe.

Also proving difficult were the segmented warp pylons,

which had been added as a complimentary component to the neck boom.

Being able to pull the warp nacelles close to the protective underside of the ship

was thought to be an additional battle advantage, as a damaged or destroyed warp

nacelle could prove as crippling to a warship as having its command pod severed

from the secondary hull. But just as with the neck boom, getting the warp

pylons' ducts,

cabling, and especially the delicate warp intermix conduits to successfully mate

across collapsing segments, proved devilish. The first few times the

collapsing pylons were tested, all power to the nacelles was shorted, and cracks

in the intermix conduits began venting white-hot plasma onto the adjacent

components. The nacelles themselves almost had to be jettisoned before the

situation was brought under control, and for the third time, the D-39 prototype

was taken back into dock for a serious review of the engineering obstacles being

faced.

Like with the boom, it was determined that successful

extension or retraction would be made easier, if the nacelle didn't have to be

in operation during the extension/retraction process. Thus the D-39 would

be on impulse power alone during the time it took for the intermix

conduits to be evacuated, their endpoints sealed, and the pylons completely

extended or retracted—a period during which, it would later been seen, the D-39

would prove unfortunately vulnerable.

Even so, with these design problems partially

mitigated, the D-39 was shaping up to be a formidable warship. A trio of

powerful, bow-mounted torpedoes gave the D-39 a tremendous offensive punch,

complimented by an array of medium and heavy disruptors which drew off the

D-39's considerable power reserves.

Internally, the D-39 was getting quietly positive

reviews for its spaciousness—a feature not commonly found on most Imperial

warships. Especially the floor-to ceiling portholes and bay windows on the

decks of the command pod. All of which afforded gorgeous

naked-eye views of surrounding space.

The D-39 also integrated state-of-the-art computer controls and

technology, including the new multi-function, multi-display LCARS-style work

surfaces—commonly seen on newer-generation Federation ships being

produced.

When the prototype D-39 finished trials and was

declared fit for commissioning in 2294 A.D., it was arguably the most powerful

and advanced Klingon warship ever built, and its debut in the fleet caused

quite a stir among both detractors and proponents. An initial production

run of fifteen D-39s was ordered, to be completed no later than the end of the

following Imperial year, and both Azetbur and her High Council were hopeful that

the introduction of the D-39, alongside the growing ranks of the considerable

L-24, would do much to deter Romulan hostility. And allow the UFP-allied Empire

to finally quash the anti-Khitomer factions still operating within the empire—factions which were straining UFP relations, on account of their destruction of

Starfleet shipping, and the theft of UFP goods.

The first real test of the D-39 came in late 2294 A.D.,

when the ship of the line—Shelled Predator—intercepted a trio of

renegade Klingon K'tinga class cruisers which were attacking a small squadron of

Federation

Aakenn class

freighters, bound for Quo'nos as part of the post-Praxis reconstruction effort.

Having dispatched the Aakenn squadron's compliment of

Remora class escorts, the

advanced K'tingas closed with the Federation freighters, demanding that the

merchantmen surrender and prepare to be boarded. The Shelled Predator—on standby watch less than half a light minute from the scene of the action—responded to the Federation freighters' distress calls.

And immediately placed

itself in the path of the renegade K'tingas, allowing the Aakenn class ships to

jump to warp while Shelled Predator dealt with its pirate cousins.

Assuming a standard tactical triangle, the K'tingas

opened fire immediately, placing several torpedo and disruptors shots into the

main body of the D-39 while the D-39's commander retracted both warp nacelles

and command pod. With shields not yet erected, the armor plate worked as

intended, and the D-39 was able to continue to maneuver without ill

effect; volleying a triple-burst from the bow torpedo bays into the

starboard wing of the lead K'tinga. That ship was nearly split in two, and

was sent pinwheeling into the void, trailing a curtain of plasma and debris in

its wake, while the remaining two renegades again placed solid hits on the

Shelled Predator. This time to be absorbed by the battle-cruiser's advanced

shielding systems. The D-39 was able to turn and disable a second K'tinga with a

barrage of disruptor strikes before the remaining K'tinga decided the day was

not to be had, and jumped away at warp speed. Shelled Predator

pursued at warp, and used its bow torpedoes to obliterate the remaining K'tinga,

before returning at warp to the original scene of the crime, where the wrecks of

the first two K'tingas were inspected for signs of life.

Klingons being Klingons, the crew of Shelled Predator

took no prisoners. When the command pods for the first two K'tingas were

located—each fleeing on impulse power—the commander of the Shelled Predator

unceremoniously atomized both vehicles.

And thus Azetbur's government secured the first of many victories it would need to crush the rebellion and secure the peace;

both for the sake of the Empire and for the sake of the Khitomer Accords,

without which the Empire was liable to expire.

The D-39's first action against a foreign enemy came in

2295 A.D. when two D-39s, the General T'choth and the Flaming Blade,

working in concert along the Romulan/Klingon border, surprised a small flotilla

of Romulans operating within Klingon boundaries. What caused the mixed

group of T-10s and

V-7s to penetrate the border is still not clear, suffice it

to say that as soon as they were bounced by the D-39s, they turned and opened

fire on the Klingon ships. Despite the fact that there wasn't a single vessel in

the Romulan group which had a chance against the D-39, head-to-head. Both

the Flaming Blade and the General T'choth immediately activated

their retraction equipment, and endured almost two minutes of withering fire

from the Romulans before the Klingon heavy cruisers had completed their

battlestations procedures. Then the D-39s came

out swinging, again using their formidable triple-bay torpedo launchers in

the forward arc. The D-39s smashed a V-7 and two T-10s with a single combined

volley, before having to maneuver against the remaining Romulans, who had

scrambled into a loose halo surrounding the Klingons.

Damage taken during the melee, was serious. As the

T'choth and Blade hammered the Romulans in ones and twos, the

Romulans used their superior numbers to collectively pepper the big Klingon

ships with torpedoes, plasma shots, and disruptor beams. The D-39s quickly saw

their shields compromised, at which point the armor plating began to take the

full brunt of the attack. T'choth received a particularly

concentrated series of hits on the dorsal surface of its port wing, to such an

extent that the ablative plating was eventually eaten through and the main hull

began to take damage. T'choth's commander promptly inverted his

craft, taking advantage of the ventral armor of his ship, but in the process

exposed his starboard warp nacelle to the Romulans. That nacelle was

demolished by several torpedo hits, at which point it exploded and

caused extensive secondary damage to the starboard wing.

Fearing the demise of the T'choth, the

Blade's commander promptly ordered his ship into the line of fire and began

taking hits.

It seemed—for a few tense moments—that the Blade

was about to meet the same fate as its brother.

Which makes it all the more strange that the Romulans

broke off their attack, regrouped, and fled across the border at high warp.

The two D-39s, one operational and one critically

damaged, were left to drift through a debris field composed of the blasted

remains of as many as a dozen Romulan craft. Taking its wounded brother in

tow, the Flaming Blade made for the nearest defense outpost. When

news of the incursion and battle reached the High Command, there was talk that

war with the Romulans might be afoot, and all border stations were put on high

alert as the Klingons, with UFP support, readied for the worst.

Fortunately for all parties concerned, the worst never

came. No massed Romulan strike ever occurred. Some in the High

Command began to suspect that the Romulan flotilla, comprised of capable but

older cruisers and destroyers, had simply been bait intended to lure the D-39

into a firefight, during which the performance of the Empire's new weapon could

be examined in detail by the Romulans. Data records from the Flaming

Blade and General T'choth were scoured for evidence that cloaked

Romulan ships had been in the vicinity, silently observing. No such

evidence was found, but many on the High Council and in the High Command remained convinced that the D-39 had been

officially 'tested' by the Romulan Empire, and seeing as how no massed attack was

forthcoming, proponents of the D-39 suggested that the D-39 so completely

outmatched the Romulans, its prowess in battle was

enough to convince the Romulans that open war with the Klingon Empire, at that

time, was not desireable.

In any case, General T'choth spent five months

in dock as its internal damage was repaired, a new warp nacelle was fitted, and

new ablative plating 'snapped' into place. Flaming Blade was

operational again within just ten days of the event, having had its damaged

armor plates 'snapped' off and replaced with fresh ones which were quickly

'snapped' on.

The first operational loss of a D-39 came in 2296 A.D.

when the Blood Warrior was dispatched to investigate the disappearance of

an L-24 and three

L-9s near Federation space. Upon arrival at the scene

of the L-24's last known sensor contact, the Blood Warrior began scouring

an adjacent starsystem for signs of foul play. Unfortunately for the

Blood Warrior, foul play is exactly what the L-24's commander had in mind.

Using the large moons of a gas giant planet for cover, the L-24 and its L-9s

jumped the Blood Warrior from two directions, loudly declaring their

rebellion across subspace and calling on the captain of the Blood Warrior

to join them in their, "Glorious return to the way of the True Klingon!"

The Blood Warrior immediately went to

battlestations, at which point disaster struck when both the retracting neck

boom and retracting warp nacelles shrieked to a halt in mid-retraction.

Paralyzed, the Blood Warrior lay completely helpless before the

onslaught. It took the renegade L-24 and L-9s only a couple of minutes to

shred the Blood Warrior with torpedo and disruptor strikes, and only the

Blood Warrior's emergency recorder buoy was later recovered by an

Imperial investigation team.

The L-24 and L-9s eventually crossed into Federation

space, wreaking much havoc before being brought down by a Starfleet task force

composed of two Excelsior class ships, a Constitution Refit, and two

Chandley class frigates.

For Azetbur's government, it was a significant embarrassment, and critics of the

D-39s unorthodox configuration renewed their accusations that the D-39 was an

essentially unsound design. All fifteen of the remaining A-model D-39s

were returned to dock, and a lengthy investigation was carried out to determine

how both the boom and the nacelles could have seized at precisely the same

moment on the same ship, in spite of the Blood Warrior having an

outstanding maintenance record prior to her final, fatal mission.

The fault was eventually traced to a computer software

glitch, wherein a command thread telling the neck and pylon servos to retract,

was partially overridden by a thread telling the servos to extend. Half the servos

went one way, the other half went the other way, and the resulting stall and

internal buckling cut off not only power to the ship's thrusters

and weapons, but maneuver control as well.

All D-39s necessarily had

their software revamped and upgraded, but

among command officers across the empire, damage to the D-39's reputation was

permanent. Several commanders refused to be considered for captaincy

of the next batch of B-model D-39s then being planned, and those remaining in

command of the existing A-model ships began eschewing the retraction process

altogether, preferring to instruct their engineers to disconnect the retraction

equipment and fuse the boom and pylon segments—thus rendering the spaceframe

'conventional' and, to the minds of the men who made the decisions, safe to

operate.

Talk on the High Council was that the D-39 might have

to be abandoned, and competing consortiums who originally lost the Klingon-Excelsior

competition began appealing to sympathetic ears that the competition be

re-opened and a new hull chosen to replace the "failed" D-39.

Korrd and the High Command discussed their dilemma at

length. A tremendous amount of time, material, and money had been expended

on the D-39, and Korrd was personally loathe to give up on his "child"

project. Thus it was promised that the next production run of D-39s, now being

dubbed the C-model, would come in two varieties: one which kept the complex

extension/retraction equipment, and one which came with the extension/retraction

equipment removed, and the segmented components of the boom and pylons fused in-place, per the habit

of the previously mentioned A-model commanders.

Thus the C-model went to the yards in 2298 A.D., with upgraded

weaponry and torpedo technology, a slightly stronger internal frame, and two

options for prospective commanders to choose from: a 'fixed' model and a

'variable' model. This would be the pattern for both D and E models, until

the time when the final production D-39 left the yards in 2338 A.D.

Following the debut of the C-model, all A-model craft

were returned to the yard for C-model refit, starting in 2298 A.D. and ending in

2305 A.D.

The D-model emerged in 2310 A.D. with improved shield

systems, a more powerful impulse deck, and an upgraded torpedo. All

C-model ships then in service were returned to the yards for D-model refit from

2312 through 2320, while new production on the D-model continued until the

advent of the E-model in 2330 A.D.

The E-model saw yet another upgrade in its impulse

efficiency, combined with upgraded warp output, a new central computer system,

and, perhaps most importantly, the addition of a cloaking device.

At the time of the D-39's conception, cloaking technology for such massive

spacecraft was not available in the Empire. But by 2330 advances in the

Klingon design of cloaking devices allowed the many larger-model craft to begin

mounting them. All new E-model D-39 warships came equipped with a cloaking

device, and all previous models of D-39 then in service were returned to the

yards for refit to E-model standards, including installation of a cloaking

device, from 2334 through 2348.

The F-model was not an actual production craft, but

rather an upgrade to the E model; an emergency refit hastily planned following

the breakout of hostilities between the Alpha and Beta quadrants, and the Gamma

Quadrant tyranny known as The Dominion. From 2370 through 2373 A.D. all

D-39s still in service were returned to the yards for quick installation of new

disruptor and torpedo technology, along with improved shielding systems and

additional ablative armor. It was hoped that such upgrades would allow the

aged D-39 to better compete with the fearsome Jem'hadar warships then being

encountered. And, along with a host of other old Klingon designs, the D-39 was

hurled into battle against not only the Jem'hadar, but also the Cardassians, and

even—unfortunately—Federation ships.

It was during the period between 2371 and 2376 that the

D-39 achieved its greatest triumphs and suffered its most ignoble defeats.

Problems with the retraction/extension system continued to crop up, sometimes

with terrible consequences for the crews involved. During the invasion of

Cardassian space—and the Empire's eventual repulsion from Cardassia via the

Jem'hadar—no less than thirty five D-39s were

destroyed or crippled in combat. An additional fifteen sustained heavy

damage, which put them out of use for the remainder of the war, and all the

rest were cast into the maelstrom that marked the final months of the conflict.

When all was said and done, the D-39 would number just 32 vessels, all

of them being E-models,

including those still in dock and undergoing repairs at the time hostilities

ceased.

As of 2378 the D-39 is at the end of its life cycle,

almost a century after it was first conceived. Perhaps not

surprisingly, only ten of the remaining 32 ships are of the

"variable" sort, with the others being "fixed". Because of the huge number of ships lost by the

Empire during the Dominion invasion, the remaining D-39s are being retained on

active service until the number of newly-constructed Klingon ships can be

brought up to sufficient levels to warrant the decommissioning of the elderly

D-39. Some notable Houses in the empire, most of them having either been

part of the D-39 consortium in the last century, or having worked as a

subcontractor during construction, have made it known that they would like to

purchase decommissioned D-39 hulls for private House use. Thus the D-39

might still be operating into the 2380s and beyond, depending on how well its

owners are able to maintain it—given diminishing replacement parts and the

antiquated nature of much of the D-39's core technology. |